The wine from Gapes of Wrath

“𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐠𝐨𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐥𝐢𝐯𝐞 𝐛𝐞𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐚𝐟𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐝𝐢𝐞.”

That is what John Steinbeck, the Iconic American Novelist wrote when he presented the vagaries of the migrant workers in his Pulitzer Prize winning work in 1939, "𝑇ℎ𝑒 𝐺𝑟𝑎𝑝𝑒𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝑊𝑟𝑎𝑡ℎ".

The book raised a storm in California whose backdrop he built the narrative. One County Banned the book for almost one and half year. But that neither stopped Steinbeck from becoming most celebrated writer in the United States nor the book from winning a Pulitzer and talking to the conscience of millions who read it even now.

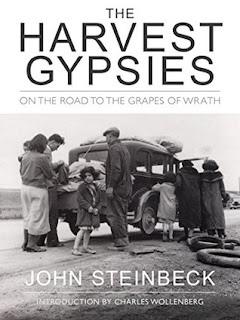

Steinbeck did not spin it as a fiction out of thin air or Hearsay. He had done a series of trips and followed the lives of the migrant workers early ‘30s and based on which he had written a set of essays released in as “𝑇ℎ𝑒 𝐻𝑎𝑟𝑣𝑒𝑠𝑡 𝐺𝑦𝑝𝑠𝑖𝑒𝑠: 𝑂𝑛 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝑅𝑜𝑎𝑑 𝑡𝑜 𝑡ℎ𝑒 𝐺𝑟𝑎𝑝𝑒𝑠 𝑜𝑓 𝑊𝑟𝑎𝑡ℎ”. These Essays raise a very interesting and important parallels with today and contrasts that need study with compassion and thought about future.

The parallels are with respect to the lives of the migrant workers as a class, their plight, the exploitation and stigma they faced. It might be surprising today for us in India to talk and to see that a prosperous developed Nation like the United States had at one time 3.5 million people moving out of the ‘Dust Bowl States’, like, Oklahoma, Arizona and Arkansas in search of Livelihood and seeing themselves as migrant workers across states like California where there was a need for extra hands during Harvesting seasons.

As a huge pool of unorganized work force that was literally selling themselves for pittance, they led a life of great hardship and meagre means. The haunting photographs that Dorothea Lang shot of these people and lives have made them immortal.

Almost after a century, much has not changed, at least for us. If we take the migrant work force from the poor states to the comparatively well-developed states in India, his words still ring true. Almost as a universal fact, the Migrant workers are considered as a necessary evil that powers our construction, Garment, Hospitality, Farming and allied industries.

“𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐢𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐧𝐞𝐞𝐝𝐞𝐝, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐡𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝. 𝐀𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐢𝐧 𝐚 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐟𝐢𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐥𝐢𝐤𝐞 𝐚𝐥𝐰𝐚𝐲𝐬 𝐦𝐞𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐛𝐲 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐞𝐢𝐠𝐧𝐞𝐫, 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐨𝐮𝐭𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐝𝐞𝐫. 𝐓𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐡𝐚𝐭𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐞𝐫 𝐨𝐜𝐜𝐮𝐫𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐡𝐨𝐥𝐞 𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐡𝐮𝐦𝐚𝐧 𝐡𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐲, 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐨𝐬𝐭 𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐦𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐯𝐞 𝐯𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐚𝐠𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐦 𝐭𝐨 𝐨𝐮𝐫 𝐨𝐰𝐧 𝐡𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐥𝐲 𝐨𝐫𝐠𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐳𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧𝐝𝐮𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐚𝐥 𝐟𝐚𝐫𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐠. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐢𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐡𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐝 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐥𝐥𝐨𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐨𝐧𝐬, 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐢𝐠𝐧𝐨𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐭 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐝𝐢𝐫𝐭𝐲 𝐩𝐞𝐨𝐩𝐥𝐞, 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐜𝐚𝐫𝐫𝐢𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐞, 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐫𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐧𝐞𝐜𝐞𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐩𝐨𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐭𝐚𝐱 𝐛𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐬𝐜𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐢𝐧 𝐚 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐦𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐨 𝐨𝐫𝐠𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐳𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐜𝐚𝐧, 𝐬𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐲 𝐛𝐲 𝐫𝐞𝐟𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐨 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐤, 𝐰𝐢𝐩𝐞 𝐨𝐮𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐞𝐚𝐬𝐨𝐧’𝐬 𝐜𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐬.”

“𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐦𝐢𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐛𝐲 𝐧𝐚𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞. 𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐠𝐲𝐩𝐬𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐛𝐲 𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐜𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐜𝐢𝐫𝐜𝐮𝐦𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬.”

Almost all of them come from impoverished and backward states where the Caste and religion have set the lives in misery and harsh outdated Feudal oppression has set the law of the land.

“𝐓𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐭𝐥𝐞 𝐟𝐚𝐫𝐦 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐬 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐝𝐞𝐦𝐨𝐜𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐲 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐨𝐧𝐥𝐲 𝐩𝐨𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐛𝐥𝐞 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐯𝐢𝐭𝐚𝐛𝐥𝐞, 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐩𝐨𝐩𝐮𝐥𝐚𝐫 𝐠𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭, 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐩𝐫𝐚𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐞𝐝 𝐢𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐆𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐠𝐞, 𝐢𝐧 𝐜𝐡𝐮𝐫𝐜𝐡 𝐨𝐫𝐠𝐚𝐧𝐢𝐳𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐨𝐫 𝐢𝐧 𝐥𝐨𝐜𝐚𝐥 𝐠𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭, 𝐰𝐚𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐩𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐛𝐢𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐲 𝐨𝐟 𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐲 𝐦𝐚𝐧. 𝐀𝐧𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐭𝐫𝐲 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞, 𝐛𝐞𝐜𝐚𝐮𝐬𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐧𝐞𝐜𝐞𝐬𝐬𝐚𝐫𝐲 𝐭𝐨 𝐦𝐚𝐤𝐞 𝐚 𝐥𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐧𝐠, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐧𝐨𝐭 𝐚𝐥𝐥𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐝 𝐚𝐧𝐲 𝐯𝐨𝐭𝐞 𝐰𝐡𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫, 𝐛𝐮𝐭 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐚 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐥𝐲 𝐮𝐧𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐥𝐞𝐝𝐠𝐞𝐝 𝐜𝐥𝐚𝐬𝐬.”

We think the churn of the un-organised sector overflowing with them is a madness that is typical of a rush to become a Developed nation. Many even defend that saying that this is a sign indicating that we are a fast-developing nation - those super power dreams notwithstanding. However, what Steinbeck showed back then, is that there is a pattern to this madness which is set up to exploit the situation and it is never an accident.

“𝐅𝐨𝐫

𝐢𝐭 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐞𝐧

𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐡𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐭 𝐨𝐟

𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐬

𝐚𝐬𝐬𝐨𝐜𝐢𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬

𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐞

𝐭𝐨 𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞

𝐛𝐲 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐨𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧,

𝐭𝐰𝐢𝐜𝐞 𝐚𝐬 𝐦𝐮𝐜𝐡

𝐥𝐚𝐛𝐨𝐫 𝐚𝐬 𝐰𝐚𝐬

𝐧𝐞𝐜𝐞𝐬𝐬𝐚𝐫𝐲,

𝐬𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐰𝐚𝐠𝐞𝐬

𝐦𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐭 𝐫𝐞𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐧

𝐥𝐨𝐰. 𝐇𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞

𝐡𝐮𝐫𝐫𝐲, 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐢𝐟

𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐢𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐭

𝐢𝐬 𝐚 𝐥𝐢𝐭𝐭𝐥𝐞

𝐥𝐚𝐭𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐜𝐞𝐬

𝐦𝐚𝐲 𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐛𝐞 𝐟𝐢𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐝

𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐥

𝐡𝐚𝐯𝐞 𝐭𝐚𝐤𝐞𝐧

𝐡𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐩 𝐟𝐨𝐫

𝐧𝐨𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠.”

“𝐖𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐧𝐞𝐞𝐝 𝐮𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐜𝐚𝐥𝐥 𝐮𝐬 𝐦𝐢𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐬, 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐧 𝐰𝐞’𝐯𝐞 𝐩𝐢𝐜𝐤𝐞𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐢𝐫 𝐜𝐫𝐨𝐩, 𝐰𝐞’𝐫𝐞 𝐛𝐮𝐦𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐰𝐞 𝐠𝐨𝐭 𝐭𝐨 𝐠𝐞𝐭 𝐨𝐮𝐭.”

This was starkly evident when the migrant workers were left to fend themselves during the height of Covid Pandemic where millions walked across the country, many hundreds and thousand miles fending for themselves, facing untold misery and without any systematic support. Many lost their lives on the way. The middle and upper classes justified the government saying that is unexpected and unavoidable. The same middle class that was happily clanging bells and plates to drive out Covid Demons while dishing out their apparently 'scientific arguments' defending the failure.

If one could look at what has changed for the Migrant worker even after the peak of covid times now, when the lives of the rest of the country is slowly limping back to normal, or new normal as we say, their arguments that sounded upbeat then, now rings hollow like their conscience. After all hunger is not a pandemic. Any voice of dissent and protest were quelled systematically by the application of force and intimidation that the power provided.

“𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐡 𝐨𝐰𝐧𝐞𝐫, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐧, 𝐢𝐬 𝐥𝐚𝐰; 𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐞 𝐝𝐞𝐩𝐮𝐭𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐚𝐥𝐰𝐚𝐲𝐬 𝐨𝐧 𝐡𝐚𝐧𝐝, 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐢𝐫 𝐠𝐮𝐧𝐬 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐩𝐢𝐜𝐮𝐨𝐮𝐬. 𝐀 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐚𝐠𝐫𝐞𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐭𝐮𝐭𝐞𝐬 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐧 𝐨𝐟𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐞𝐫. 𝐀 𝐠𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐥𝐢𝐬𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐦𝐢𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐭 𝐝𝐮𝐫𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚 𝐬𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐥𝐞 𝐲𝐞𝐚𝐫 𝐢𝐧 𝐂𝐚𝐥𝐢𝐟𝐨𝐫𝐧𝐢𝐚 𝐟𝐨𝐫 “𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐧 𝐨𝐟𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐞𝐫” 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐠𝐢𝐯𝐞 𝐚 𝐟𝐚𝐢𝐫 𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐚 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐚𝐬𝐮𝐚𝐥𝐧𝐞𝐬𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐞 “𝐨𝐟𝐟𝐢𝐜𝐞𝐫𝐬” 𝐢𝐧 𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐨𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐤𝐞𝐫𝐬”

Steinbeck also presents in his later half of the essays, how positive action by active participation of government changed the situation for good. The government provided social security for these migrant workers by setting up a specific bureau for them which in turn provided housing and also sustenance by allocating lands that could keep them afloat. These measure that gave them a lifeline changed the society as a whole by changing the opinion of the larger community against the migrant workers - which always saw them with suspicion and hatred - besides providing a newfound confidence and stability for the Migrant worker communities.

“𝐓𝐡𝐞

𝐆𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐧𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭

𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐬 𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐜𝐞𝐬

𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬. 𝐏𝐞𝐫𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐞𝐧𝐭

𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐮𝐜𝐭𝐮𝐫𝐞𝐬

𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐬𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞,

𝐢𝐧𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠

𝐰𝐚𝐬𝐡𝐫𝐨𝐨𝐦𝐬,

𝐭𝐨𝐢𝐥𝐞𝐭𝐬 𝐚𝐧𝐝

𝐬𝐡𝐨𝐰𝐞𝐫𝐬, 𝐚𝐧

𝐚𝐝𝐦𝐢𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧

𝐛𝐮𝐢𝐥𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐚𝐧𝐝

𝐚 𝐩𝐥𝐚𝐜𝐞 𝐰𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞

𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐩𝐞𝐨𝐩𝐥𝐞

𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧

𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐦𝐬𝐞𝐥𝐯𝐞𝐬.

𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐞𝐪𝐮𝐢𝐩𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭

𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐀𝐫𝐯𝐢𝐧

𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐩, 𝐞𝐱𝐜𝐥𝐮𝐬𝐢𝐯𝐞

𝐨𝐟 𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞

𝐥𝐚𝐧𝐝, 𝐜𝐨𝐬𝐭𝐬

𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐱𝐢𝐦𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐥𝐲

$𝟏𝟖,𝟎𝟎𝟎. 𝐀𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐬

𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐩, 𝐰𝐚𝐭𝐞𝐫,

𝐭𝐨𝐢𝐥𝐞𝐭 𝐩𝐚𝐩𝐞𝐫

𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐬𝐨𝐦𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐝𝐢𝐜𝐚𝐥

𝐬𝐮𝐩𝐩𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞

𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐯𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐝. 𝐀

𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐭 𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐚𝐠𝐞𝐫

𝐢𝐬 𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐠𝐫𝐨𝐮𝐧𝐝.

𝐂𝐚𝐦𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐬 𝐚𝐫𝐞

𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐞𝐢𝐯𝐞𝐝 𝐨𝐧

𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐨𝐥𝐥𝐨𝐰𝐢𝐧𝐠

𝐬𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐥𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐝𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬:

(𝟏) 𝐓𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐞𝐧

𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐛𝐨𝐧𝐚 𝐟𝐢𝐝𝐞

𝐟𝐚𝐫𝐦 𝐩𝐞𝐨𝐩𝐥𝐞

𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐝

𝐭𝐨 𝐰𝐨𝐫𝐤, (𝟐) 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭

𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐡𝐞𝐥𝐩

𝐭𝐨 𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧

𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐥𝐞𝐚𝐧𝐥𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐬𝐬

𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐩

𝐚𝐧𝐝 (𝟑) 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐧

𝐥𝐢𝐞𝐮 𝐨𝐟 𝐫𝐞𝐧𝐭

𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐲 𝐰𝐢𝐥𝐥 𝐝𝐞𝐯𝐨𝐭𝐞

𝐭𝐰𝐨 𝐡𝐨𝐮𝐫𝐬 𝐚

𝐰𝐞𝐞𝐤 𝐭𝐨𝐰𝐚𝐫𝐝𝐬

𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐢𝐧𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞

𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐫𝐨𝐯𝐞𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭

𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐩.”

“𝐈𝐧

𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐲𝐞𝐚𝐫 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭

𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐀𝐫𝐯𝐢𝐧 𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐩

𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐛𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐢𝐧

𝐨𝐩𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧

𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐧𝐨𝐭

𝐛𝐞𝐞𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐲 𝐧𝐞𝐞𝐝

𝐟𝐨𝐫 𝐨𝐮𝐭𝐬𝐢𝐝𝐞

𝐩𝐨𝐥𝐢𝐜𝐞. 𝐏𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐬𝐡𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐭𝐬

𝐚𝐫𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐫𝐢𝐜𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧𝐬

𝐨𝐟 𝐜𝐞𝐫𝐭𝐚𝐢𝐧

𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐯𝐢𝐥𝐞𝐠𝐞𝐬

𝐬𝐮𝐜𝐡 𝐚𝐬 𝐚𝐝𝐦𝐢𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧

𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐦𝐮𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲

𝐝𝐚𝐧𝐜𝐞𝐬, 𝐨𝐫 𝐟𝐨𝐫

𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐮𝐞𝐝

𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐢-𝐬𝐨𝐜𝐢𝐚𝐥

𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐝𝐮𝐜𝐭, 𝐚 𝐫𝐞𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐦𝐞𝐧𝐝𝐚𝐭𝐢𝐨𝐧

𝐭𝐨 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐚𝐧𝐚𝐠𝐞𝐫

𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐩𝐫𝐢𝐭

𝐛𝐞 𝐞𝐣𝐞𝐜𝐭𝐞𝐝

𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐩.”

“𝐈𝐧 𝐯𝐢𝐬𝐢𝐭𝐢𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐬𝐞 𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐩𝐬 𝐨𝐧𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐢𝐦𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐬𝐞𝐝 𝐰𝐢𝐭𝐡 𝐬𝐞𝐯𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐭𝐡𝐢𝐧𝐠𝐬 𝐢𝐧 𝐩𝐚𝐫𝐭𝐢𝐜𝐮𝐥𝐚𝐫. 𝐓𝐡𝐞 𝐬𝐮𝐥𝐥𝐞𝐧 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐟𝐫𝐢𝐠𝐡𝐭𝐞𝐧𝐞𝐝 𝐞𝐱𝐩𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐬𝐢𝐨𝐧 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐢𝐬 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐫𝐮𝐥𝐞 𝐚𝐦𝐨𝐧𝐠 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐦𝐢𝐠𝐫𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐬 𝐡𝐚𝐬 𝐝𝐢𝐬𝐚𝐩𝐩𝐞𝐚𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐟𝐫𝐨𝐦 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐟𝐚𝐜𝐞𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐭𝐡𝐞 𝐅𝐞𝐝𝐞𝐫𝐚𝐥 𝐜𝐚𝐦𝐩 𝐢𝐧𝐡𝐚𝐛𝐢𝐭𝐚𝐧𝐭𝐬. 𝐈𝐧𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐝 𝐭𝐡𝐞𝐫𝐞 𝐢𝐬 𝐚 𝐬𝐭𝐞𝐚𝐝𝐢𝐧𝐞𝐬𝐬 𝐨𝐟 𝐠𝐚𝐳𝐞 𝐚𝐧𝐝 𝐚 𝐬𝐞𝐥𝐟-𝐜𝐨𝐧𝐟𝐢𝐝𝐞𝐧𝐜𝐞 𝐭𝐡𝐚𝐭 𝐜𝐚𝐧 𝐨𝐧𝐥𝐲 𝐜𝐨𝐦𝐞 𝐨𝐟 𝐫𝐞𝐬𝐭𝐨𝐫𝐞𝐝 𝐝𝐢𝐠𝐧𝐢𝐭𝐲.”

Today, in India there is a motivated move to denounce such positive actions as “freebies” and clamour for stopping them in the name of drain of public funds. This is nothing new. Steinbeck records similar voices during his time and also the counter arguments in favour of such positive measures that lead to long-term benefit of the larger society.

Contrary

to what we do here to deny and suppress such criticisms, In the end the saner

voices prevailed in the US and government steadfastly followed through them.

Today, if somebody of Stature of Steinbeck in India raises such a criticism, he

would have branded anti national first by the privileged class. So, expecting a

positive action is a pipe dream to say the least.

Comments

Post a Comment